Changes in grain production across the DPRK were divided into three periods, i.e., continuous growth, violent fluctuation, and slow recovery. The data showed that grain production within the DPRK more than doubled from 4 million tons to 9.835 million tons over the period between 1961 and 1991.

It is clear that the period between 1992 and 1997 was characterized by violent fluctuations in grain production. This value dropped sharply from a peak of 3.35 million tons (1996) to a value even lower than that seen in 1961. A slow recovery between 1998 and 2019 meant that DPRK grain production gradually increased to the 1975 level, that was 6 million tons.

The staple grain crop in the DPRK comprises rice and maize. Rice is the main component of grain production, providing at least 43% of grain supply, and maize is the second major constituent. The proportion of maize out in the total grain production decreased significantly throughout the 1990s, while wheat production across the DPRK remained low. Beans production nationally remained relatively stable, while potato has been an important staple for the DPRK since the 1990s. A high potato yield could effectively alleviate grain shortages.

[…]

The United Nations FAO believes that it is safe for a country to reach 400 kg per capita of grain possession [38]. In this context, and according to the DPRK grain supply and consumption situation, this relationship transitioned from a ‘supply and consumption balance’ to a ‘supply exceeding consumption’ situation between 1961 and 2019 (Figure 4). This transition can be divided into two stages encompassing food and clothing (between 1961 and 1994) and poverty (between 1995 and 2019).

Thus, between 1961 and 1994, the DPRK actually achieved grain self-sufficiency and reached a basic balance between supply and consumption. Data show that per capita grain possession was basically maintained over this period at about 400 kg and that in some years it rose close to 490 kg.

Subsequent to 1995, however, grain production within the DPRK dropped sharply; considering imports and international assistance, per capita grain possession remained at about 260 kg around this time. It is noteworthy that since the implementation of international aid to the DPRK around 1995, more than 400,000 tons of grain was received each year. This equates to a cumulative total of more than 12 million tons.

However, as the DPRK population has grown rapidly, pressures on the grain supply have also greatly increased. Ensuring an adequate grain supply remains a major problem that will need to be solved in the future.

[…]

(1) It is clear that prior to 1992, the DPRK experienced a ‘golden period’ characterized by continuous improvements in grain production capacity [8–11]. The agricultural production levels throughout this period exceeded even those of China. Thus, the DPRK can solve the current grain problem by implementing an agricultural management system or a series of technological innovations [15].

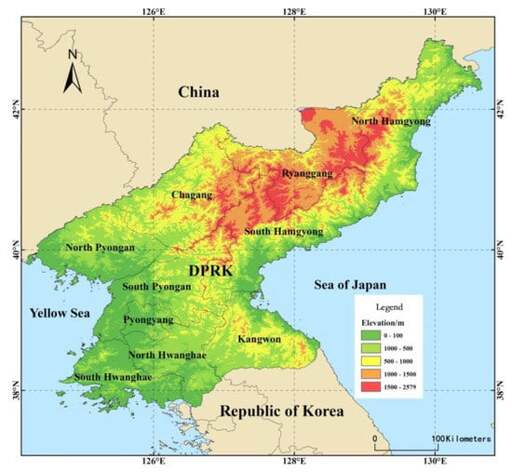

(2) The DPRK possesses favorable natural and water conservancy infrastructural conditions that can facilitate a substantial increase in its grain production capacity. As long as fertilizer production capacity and management levels are enhanced, the DPRK will maintain a significant potential to increase grain production [19].

(3) China and the DPRK are geographically close and related to each other historically. There is thus great potential to promote agricultural cooperation, especially in grain production, given the significant improvements on the Korean Peninsula since 2018.

(Emphasis added.)

The rest of the paper is a general analysis of the DPRK’s agriculture. You can tell that it’s maturely written since it does not toss around buzzwords such as ‘dictator’, ‘authoritarian’, ‘totalitarian’, or ‘hermit kingdom’ and the like; it also finds mundane reasons for the present difficulties in the DPRK’s agriculture, rather than either simply omitting the reasons or immediately blaming undefined phenomena like ‘collectivism’ or ‘communism’ (with the implication being that neoliberalism is the panacea). Overall, a worthwhile read, though it is a little technical.

A sobering remark from page 2:

no comprehensive multisource data analysis has so far been presented to assess grain supply and consumption within the DPRK.

(This was written in 2022.)

Industrial Agriculture Lessons from North Korea I hope this is the article you are talking about.

Fantastic overview of agriculture in the DPRK and the huge shifts they have endured. The current trends and practices of the DPRK could be a useful insight for agricultural production that is less dependent on Fertiliser.

Yea that’s the article.

Still, i think communists should not adopt this line of thinking that sees industrial agriculture as bad. From my own experience, the largest problem in the industry is a nepotism/property problem and the dialectic between farmers and input businesses, land gets inherited by people that are not specialized in agriculture and they have to rely on the advice of private “agricultural engineers” (they are actually merchants) that have a vested interest in overselling you products. Inputs will always be necessary in a open loop practice like agriculture (output gets exported away from the soil, you need inputs to replenish the soil), it’s just a matter of efficiency, having professionals be in charge of production instead of uneducated people that happened to inherit the soil.

It gets especially bad in countries that enacted some sort of land reform that ended up atomizing land into small plots for individual peasants.

I’m not saying that you’re wrong, but I have yet to see a single communist that is opposed to industrial agriculture.

I think the vast majority of communists, and people in general, agree that industrial agriculture is one of the primary methods that humanity is able to feed so many people.

As you said, I think the main issues are the dialectic between farmers, workers, businesses, and the overabundance of pesticide/gmo usage.

Pesticides and GMO’s definitely have their place, but as with everything, moderation is key.

There’s a big overlap between communists and vegans, so yeah I’m really opposed to animal farming (it’s heavily industrialized)

If you think agriculture isn’t also heavily industrialized, I have a bridge to sell you.

Sure you can have some idyllic fields, but that wont feed many people.

Please re-read what I wrote. I said animal agriculture is bad. I didn’t say anything about plant agriculture. I’m ok with industrial plant ag but I hate animal ag

I guess what i meant is leftists in general tend to idealize small scale agriculture and demonize large scale agriculture, it’s a very common belief tbh its great that you haven’t seen much of it.

Leftists might, communists don’t.

I think much of the debate is the comparison of how the DPRK is faring with how Cuba has adjusted. Cuba faced extremely similar problems with loss of industrial fertilizers from the USSR’s oil. They adapted by embracing organic agriculture instead of industrial agriculture such that today, Cuba is probably the closest to an ecosocialist country of anywhere in the world. Take a look at Cuba’s organoponicos.

Unfortunately, while this has made Cuba much more self-sufficient, this hasn’t fixed the fact that Cuba still needs to import some food. Before they were an exporter of sugar, while now they are still a food importer.

Ultimately, while such initiatives are nice, and do make us healthier, it really can’t be embraced that much, lest we all starve to death. This has the same kind of vibe as coddled white liberals telling Africans to stay poor and not to mine their resources because “it’s bad for the environment.”